RTTP:Great Depression

From EDiT

Context for the Great Depression

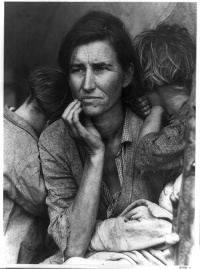

To understand the Great Depression we should understand the term "depression." The term "depression" had been used by economists to describe severe economic downturns for many decades prior to the 1930s and this has been the conventional meaning of the term. However, "depression" also has meaning in other fields, especially psychology. And this understanding also helps us to understand the Great Depression, as it was more than another periodic downturn in the economy. It was also a great national malaise, a moment of severe collective doubt and soul-searching that was also tinged by a profound sense of personal guilt. Perhaps a man foolishly invested in farmland when he should have saved his pennies; maybe he trusted a bank with his cash deposits and lost everything when the bank closed. He had been looking for work for ten, fifteen, maybe thirty months without a single offer of employment. In any case, he can no longer provide for his family as a man ought to do; he carries a deep sense of shame that he shares with no other. He finds it embarrassing and emasculating to have to ask, beg even, for food or to accept a hand out from government or city-run soup kitchens. Women worried for their husbands and children, where the next meal would come, and how they could not keep house and home as they expected good women to do. For those whom the Great Depression touched, it touched them deeply, personally, and profoundly.[1]

Thus the Great Depression is a story about conflicting expectations. Americans had expectations about how to behave and how to be responsible by supporting oneself and one's family. They had expectations about their society and how they should care for each other. Shouldn't churches and town halls provide food for the needy? But as the severity of the Depression unfolded, even local relief agencies, such as churches, could not keep up. Towns and Schools went bankrupt from lack of tax support. It forced Americans to look at their expectations of what government should or should not do and led them to question the role of government in their lives.

The 1920s had been wildly prosperous for many (but not all), and many expected that prosperity to continue. And with an economic collapse on the scale of a national economy, some Americans began to question their expectations about the role of government in their business and personal lives. It was certain that Americans would not come out of the Great Depression with the same sorts of expectations for themselves, their careers, their financial well-being, and their government that carried them into it.

Historians and economists of the twentieth century have spent much time and effort attempting to isolate the causes of the Great Depression. In understanding the causes of the Great Depression, we can also see the expectations that Americans carried with them into the 1930s. Certainly, the prosperity and the idiosyncrasies of the 1920s economy precipitated the Great Depression, but Americans' expectations of the national government and of national prosperity begin in Progressive Era and First World War and how they re-oriented national expectations and economies.

Progressive Era

While the desire for social reform proved to be very strong during the Great Depression, it was a return of the reform sentiment to which Americans from time to time come. Many of the reformers involved in the New Deal first became active in social reform during the Progressive Era, a period of time roughly between the mid-1890s to about the 1920s. While historians have identified this entire period as the Progressive Era, reformers did not start identifying themselves with the term "progressive" until around 1910.[2]

Historians disagree on the origins of the Progressive Era (in the late twentieth century, some have even denied the existence of a "progressive movement"). It came from a variety of sources, but nearly all were influenced by the industrialization of the United States in the mid-to-late nineteenth century. This industrialization greatly expanded the economy, but also created a lot of hardship. Karl Marx in his mid-century analysis of industrialization noted that the process was dividing society into two classes: the Bourgeoisie (the haves) and the Proletariat (the have-nots). He predicted that class warfare would ultimately erase the Bourgeoisie and the Proletariat would thereafter share all the fruits of production. Socialists and communists began working towards ameliorating the harmful effects of industrialization upon workers. Not only socialists and communists but also social reformers of more traditional lines sought to ease the struggles of workers. By the end of the nineteenth century, millions of workers were putting faith in collective action through labor unions as the means to fight the industrialists and to gain some economic power for themselves.

By the late nineteenth century, labor unrest in the U.S. was becoming remarkably violent. The Homestead Strike of 1892 pitted a private army of Pinkerton detectives hired by Henry Clay Frick the president of Andrew Carnegie's steel company. Frick and Carnegie won this strike and broke the steel-workers union for the next forty years. Two years later, a more bitter strike alarmed the nation. Following the Panic of 1893, George Pullman, the president of the Pullman Company (a manufacturer of railroad passenger cars), had cut wages at his factory. But Pullman also operated a company town and when he refused to lower housing rents and commodity prices at the company store, his workers struck. Union organizer Eugene Debs turned this local Pullman Strike into a national issue with a sympathy strike by his American Railway Union (ARU). The ARU refused to handle any train containing a Pullman car; and since nearly every train carried a Pullman car, this effectively shut down the U.S. rail network. Manufacturers and businessmen howled and pressured President Cleveland to act, which he did by calling out the U.S. army to operate the railroads. There were many instances of violence. Attorney General Richard P. Olney got a favorable ruling from a court declaring Debs' labor union illegal under the Sherman Antitrust Act as a "combination in restraint of trade." So contentious and bloody were these strikes and others during the 1890s, that many Americans began to fear that Marx's predictions of bloody class war were about to come true.

That the tools and powers of the government (its courts and police) were being used against the people of the United States caused many to wonder about the decline of democracy in the U.S. Wasn't republican government ("government of the people, by the people, and for the people" as Abraham Lincoln said) under attack when the government attacked the people? Clearly people were expressing desires and needs, if not from desperation then from frustration. In many ways, people wished to care for themselves and their families. But low wages and poverty made this difficult. Would not more responsive government at both the state and national levels, government that met the needs of the people, ease the strife of the 1890s? Many thought so and sought to make government more democratic.

Others sought to ease the hardships create by industrialization. If workers could be assured of steady employment, care for themselves and their family if they were unable to work, compensation if they were injured in the workplace, and other assurances that they could provide for their families, then would not also the bitterness between worker and employer lessen? This became the aim for reformers seeking a broad body of ideas called "social insurance."

These reformers, whether they sought political reforms or economic reforms were called "progressives." These progressives included social workers such as Jane Addams and Grace Abbott, but also economists such as John R. Commons and his University of Wisconsin discipline of institutional economics.

The reformers during the Progressive Era had a difficult time breaking the legislative habits of the United States. Political and electoral reforms such as the secret ballot, the initiative, recall, referendum, and the direct election of U.S. senators seemed easier to achieve than old-age pensions, workmen's compensation, or unemployment insurance. In these matters, often collectively called "social insurance" program, progressives clearly favored greater government involvement over business and in the lives of workers. Increased government power to regulate seemed to be the only means by which these social insurance measures could be made real.

Tragedy sometimes abetted the cause of social reform as in the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire of 1912. Following the investigation into this disaster, New York began workplace safety inspections.

The presidential election of 1912 also gave a boost to progressive causes when three of the four candidates came out in favor of social reforms. In this election, Woodrow Wilson and the Democratic Party won. They were able to make some changes regarding child work laws, hours for railroad employees, and a first attempt at prohibiting the use of the injunction against labor unions, but in matters such as pensions, health insurance, workmen's compensation, and aid to dependent mothers and children no changes were made.

In 1914, the great nations of Europe started World War I and the politics in the U.S. increasingly turned towards that emergency. When United States declared war on April 6, 1917, the progressive spirit of using government towards the greater social good was used as never before. But also, the reactionary hysteria that the war brought also ended any truly progressive spirit in American politics.

The Effects of World War One

For over four hundred years prior to World War One, the great nations of Europe dominated global trade and finance. Great Britain, France, and Germany (which was created as a nation-empire in 1871) combined out-produced any other trade region in the world in all important industrial and consumer commodities. Great Britain was the world's largest creditor.

World War One changed this global economic situation. The war drained the finances of the great nations of Europe. Ever in demand of industrial products, strategic resources, and food, the western allies turned to the United States for them. Paying for these supplies transformed the western allies from the world's leading creditor nations into the world's leading debtor nations. Devoting their great merchant fleets to the importation of strategic supplies, the western allies also lost contact and trade with the rest of the world. Germany, which was blockaded for the duration of the war, lost any global economic position (as measured in trade or colonies) that it had prior to the war. Into this global economic vacuum stepped the United States.

Prior to World War One, the United States had become the world's single leading national economy, but most of its economic activity was domestic. The United States had a very limited position in international trade. But by 1915, as the world's largest economy not at war, the U.S. economy expanded dramatically. For the first time in its history, the United States became a net exporter of goods (exporting more than it imported). For example, the exportation of wheat increased 700% between 1914 and 1917 and exports in zinc increased 37-fold. As a result, gold flowed into the U.S. and prices began to rise dramatically. By 1920, wholesale prices in the U.S. were about 250% what they were in 1914.[3]

The war, however, placed severe strains on U.S. economic organization. Throughout the nineteenth century, entrepreneurs, workers, and farmers engaged in economic activity for private benefit. With the U.S. declaration of war against Germany on April 6, 1917, this economic activity had to be reorganized towards public benefit. The competing demands of the U.S. government and private enterprise wracked the system. American policy makers had little experience with national economic planning and big business had little desire to let the government try. The administration of Woodrow Wilson created the Council for National Defense (CND) on which sat both cabinet officials and businessmen. Once war was declared, the CND created the War Industries Board (WIB). The WIB was a government body to organize and run the national economy but was led by big business. Bernard Baruch, who had been a wealthy trader on the New York Stock Exchange, served as the WIB director. The WIB had power to determine production priorities, set (or "fix") prices, order factories to engage in war production, and purchase supplies needed by the U.S. or its allies.

U.S. government expenses during the war expanded greatly. Prior to 1915, the annual U.S. budget never exceeded $760 million. But by April 1917, the U.S. Government was spending that amount every month. By the 1920s, the federal budget was about three times the size it had been before the war (adjusted for inflation). Also increased was the U.S. debt. In 1913, interest on the federal debt was taking about 2.3% of the federal budget, by 1927 interest was taking about 22%.[4]

Was it worth it? What were the lessons learned? The U.S. Department of Commerce argued that the command economy created during World War One was successful. Government intervention into the economy increased real GNP by about 18% making the command economy more efficient that the free enterprise system it replaced.[5] So by one measure government intervention during a national emergency brought about beneficial change.

Savings

Personal savings were at an all-time high. The U.S. government financed the war through taxes and Liberty Bonds. These were small-denomination bonds sold by the government. By 1919, $21 billion had been raised through four liberty bond drives and of this amount, only about $4 billion was held by financial institutions, which means that over 80% of the bonds were held by individuals.[6] As such, patriotism was measured in personal savings; the more bonds a person bought showed their patriotic commitment to the war effort. Government agencies encouraged savings in other ways too. For example, the Food Administration led by Herbert Hoover advocated that Americans should make do without certain commodities in order that U.S. soldiers would have them. Hoover called these conservation campaigns "meatless Tuesdays," "wheatless Wednesdays," or "porkless Saturdays." In 1918 alone, Americans saved over $12.5 billion with about three-quarters of that amount invested in government securities such as the liberty bond ($8.6 billion). Annual savings would not be this high again until 1941.[7]

While the war bonds were not seen as a retirement investment, it was clear that savings were important to families in the event that the principal breadwinner could not provide. Savings provided that income during periods when the man of the house could not find work, which was expected to happen from time to time. Retirement, on the other hand, was an alien concept. Men, if they could work, were expected to work, regardless of their age, whether it be eleven or ninety-one. Because of this expectation about male work, no family saved for the day when the man would "retire" from work.

Farming

Americans conserving and cutting back on their food consumption does not mean, however, that farming was in a crisis during the war. Quite the contrary, farming had never been as productive or as profitable as it was during World War One. Between 1915 and 1919, farm income rose by over 125%.[8] But farmers did not recognize this income bubble as an aberration caused by the decline of the agricultural productivity of the European nations at war and their demand for U.S. foodstuffs. Instead American farmers expected these conditions of high demand and high prices to continue after the war. They thus took their income gains and used the money to further expand production by investing in more farmland. Farm mortgages rose nearly 400% during the same period and then by another $400 million in 1920 alone. Between 1915 and 1920, the amount of farm mortgage rose by 568% or at an average of 46% a year. The bubble burst in 1921. Farm incomes in 1921 were less than 40% what they were just two years before while banks had foreclosed on $1.683 billion of mortgaged farms. Farmers lost another $831 million to the banks over the next two years. Banks foreclosed on more farms in 1924 than during any year of the Great Depression.[9]

Prosperity and Problems in the 1920s

Unlike Europe which had been devastated by the First World War, the United States was invigorated by it. Its economy expanded, like farming, and the U.S. was the most prosperous nation on earth. This prosperity, however, was not without its problems. It was not a broad-based prosperity; some benefited much more than others and not every industrial sector expanded. But those that did benefit did so wildly and publicly. It was so widely perceived that America was enjoying a broad-based prosperity, that the period became known as the "Jazz Age."

Narrow Investments

The growth in the national economy was limited to just two sectors: automobile manufacturing and construction. If we look at construction more carefully, however, we see that most of the construction was automobile related: highway construction and other improvements needed to accommodate automobiles (parking spaces, garages, and other infrastructure improvements). Thus when the automobile sector turned soft (as it did starting in 1927), it was bound to have ripple effects and slow the national economy.

Workers generally did not benefit from the prosperity of the 1920s. In spite of the supposed wild prosperity of the 1920s, the bottom 93% of Americans were only about 6% better off in 1929 than they were in 1920.

Perceptions of Prosperity

Despite the weak fundamentals of the economy, most Americans perceived that the economy was fine and growing and that most Americans, even if they themselves were not, were growing more wealthy.

Upon his inauguration in 1929, President Herbert Hoover remarked that "I have no fears for the future of our country. It is bright with hope."

In August 1929, Ladies Home Journal published an interview with John Jacob Raskob, the former president of General Motors and chairman of the Democratic Party National Committee, in which he claimed that if the average family invested just $15 a month in the stock market during the 1920s, they would have netted a wealth of $80,000 by 1929. Rascob failed to mention that the average income during the 1920s was about $100 month.

Samuel Crowther, "Everybody Ought to be Rich: An interview with John J. Raskob," Ladies Home Journal, August 1929, 9. in 100 years of Wall Street, by Charles R. Geisst (New York: McGraw-Hill Professional, 2000), 22-23.

Understanding The Great Gatsby: A Student Casebook to

Issues, ... - Google Books Result

Dalton Gross, MaryJean Gross - 1998 - Literary Criticism - 177 pages

FROM SAMUEL CROWTHER, "EVERYBODY OUGHT TO BE RICH. AN INTERVIEW WITH

JOHN J. RASKOB" (Ladies' Home Journal, August 1929, pp. 9, 36) Being

rich is, ...

http://books.google.com/books?id=D7iRLn8ZsAIC&pg=PA155&lpg=PA155

Florida Real Estate

One of the key events that led many to believe in a wild and broad-based prosperity were fantastic booms such as the one in Florida real estate. During the mid-1920s, a speculation in Florida real estate took off. Miami's population boomed 250% between 1920 and 1925. Developers were buying and turning over lots so quickly that property values were rising at annual rates of 100-200%, sometimes even more. Miami banks originated over $1 billion in mortgages in 1926. Nearly all of it on speculation. One popular account of the 1920s, estimated that as much as 90% of the sales in Florida real estate was with the intention of reselling it as soon as possible; few buyers actually wanted to live there.

On September 18, 1926, the Great Miami Hurricane, a category 4 tropical storm made landfall at Miami and caused extensive damage. In 2008, a team of meteorologists and actuaries reported in a study for Natural Hazards Review that in real dollars, this 1926 hurricane was the most costly U.S. Atlantic hurricane in history, being nearly twice as costly in real dollars as the Katrina Huricane of 2004.[10] This devastation ended the rampant speculation in Florida real estate. Miami bank mortgage originations were down by half in 1926, and off 86% by the end of 1928.

Florida real estate, however, was not the only land speculation boom to occur in the 1920s. There was a massive speculation in farming as noted above between 1919 and 1921. Speculation in California real estate began during the decade as well. But most land speculation, in number of lots as well as in dollars, occurred in the suburbs of major U.S. cities. As the automobile made access to central cities easier and more idiosyncratic, middle-class and upper-class Americans could afford to live in the suburbs and commute to their jobs in the city. For New Yorkers, for instance, there was a development boom on Long Island, mainly fueled by wealthy investors and became the subject matter for F. Scott Fitzgerald's The Great Gatsby.

By 1928, land development everywhere in the U.S. began to slow. Markets were saturated with housing. Yet none of these development booms even came close to the frenzy that was the Florida real estate boom.[11]

A Banking Crisis

With the crash of the farmland-mortgage sector, rural banks began to go under. Most farmers did not go to New York City to secure their farm mortgage; they went to their local town bank. When these mortgages became uncollectable in the mid-1920s, these small town banks also began to suffer. While the U.S. economy moved along swiftly during the 1920s, half of all banks were insolvent and failed. These were mostly small-town banks to be sure, but that the underlying banking sector was suffering from such a high rate of failure did not bode well for the future of the larger banks. The larger, more urban banks, were having their own adventure in the Great Bull Market.

The Market Boom and Crash

| See also: | Wall Street Crash |

The "Roaring Twenties" in the U.S. was one of the most energetic and economically healthy decades of the twentieth century. One of the popular ways of making money was speculation in stocks and bonds. As the popularity of these stocks and shares grew rapidly, so did their prices. As the prices of stocks rose, the Americans were mesmerized by the stock market. Banks, too, got involved in the speculation loaning millions to speculators and brokerage houses, so much of this great bull market was fueled by debt. Even as the economy began to slow down in early 1929 and as bankers grew wary of stocks, brokerage houses and speculators kept buying. On February 28, 1929, a banker commented on the stock market, saying,

stocks look dangerously high to me. ... this bull market has been going on for long time, and although prices have slipped a bit recently, they might easily slip a good deal more. Business is none too good. Of course if you buy the right stock you'll probably be all right in the long run and you may even make a profit. But if I were you I'd wait awhile and see what happens."[12]

And this was in February just as prices began a prolonged rise that lasted through August.

Given the weakening economy, the Dow Jones Industrial Average reached its peak on September 3, 1929. It then began a slow decline to the end of October, losing about 9% of its value. On October 24, known as "Black Thursday," trading was three times normal, or about 12 million shares and most traders were selling. In an emergency session, bankers decided to buoy the market by buying stocks on Friday in order to prevent further declines. But trading was again so heavy that the banks could not keep up and decided to let the market find its own level on Monday. That Monday, the stock market fell 38 points (or over 13% of its value) which was the largest single-day drop in its history to that point, even worse than the next day, "Black Tuesday." Black Tuesday, October 29, 1929, is often identified as the single day of the crash. Traders entered the market to sell stock and the volume was a whopping 16 million shares. The Dow fell about 12% for the day. Over the two days of Monday and Tuesday, the Dow lost about a quarter of its value. With some ups and downs over the next three years, the stock market continued a downward trend. It reached the bottom in July 1932 at 41.22, which was a loss of over 89% of its value from the market high in September 1929. It would take the market until 1954 to again reach its 1929 high.[13]

The Severity of the Depression

By 1933, there were over 13 million unemployed in the U.S. which was about a quarter of the labor force.

Responses by Hoover

The Great Depression and the suffering of millions of Americans was a severe test to the believers in limited and passive government. The traditional bulwark of the Republican Party was laissez faire, which meant that government was to leave business alone and not interfere with the economy. The Secretary of the Treasury for all three Republican administrations during the 1920s, Andrew Mellon had some stern advice for Hoover. As Hoover recounted in his memoirs,

In one camp were the "leave it alone liquidationists" headed by Secretary of the Treasury Mellon, who felt that government must keep its hands off and let the slump liquidate itself. Mr. Mellon had only one formula: “Liquidate labor, liquidate stocks, liquidate the farmers, liquidate real estate.” He insisted that, when the people get an inflation brainstorm, the only way to get it out of their blood is to let it collapse. He held that even a panic was not altogether a bad thing. He said: "It will purge the rottenness out of the system. High costs of living and high living will come down. People will work harder, live a more moral life. Values will be adjusted, and enterprising people will pick up the wrecks from less competent people"[14]

While his Republican colleagues were more than willing to let Americans suffer, Hoover believed he needed to something, but something that would also be acceptable to his republican colleagues. Thus, his intervention and his proposals would be limited and as such was insufficient to the crisis.

Hoover's initial response was to reinforce traditional expectations about limited and passive government. These expectations were that the national government was responsible for the common defense and other narrowly-defined duties as described in the Constitution. Government was not responsible, according to traditional expectations, for helping people find work, bailing out industry, providing food, protecting homes from foreclosure, or guaranteeing personal savings and pensions.

Thus Hoover was in a difficult position. Limited by his party's political philosophy he should have offered little more that platitudes and cheer-leading (following Theodore Roosevelt's advice of using the presidency as a "bully pulpit") to encourage Americans to be tough and weather the crisis, which he of course did. Yet his Quaker upbringing inspired him to act. As president, Hoover ordered the government into more activities, reform, regulation, and economic intervention than any previous peace-time president. Yet, Hoover's responses were too little to affect the magnitude of the crisis and small in comparison to the activities undertaken by government in the New Deal.

In speech after speech, Hoover advocated that business do what it could to keep factories open and operating, that managers should not cut wages, or to encourage innovative "share-the-work" programs.

Farm Crisis

To address poor farm productivity, which had been languishing for much of the 1920s, Hoover turned to techniques he used while food commissioner during World War One. He proposed and pushed through Congress the Agricultural Marketing Act which established a Federal Farm Board. The farm board was partly a trade association that assisted farm cooperatives in marketing their crops and partly a federal price control. The board was empowered to purchase farm surpluses through its "stabilization corporations." The board always purchased farm products at above market prices as a means to raise market prices. The program got started in the fall of 1929 coincident with the Great Depression. Thus the government was buying crops at high prices, and had few options but to sell these crops at declining prices. Congress authorized $500 million for this project, but after just two years it had spent over $700 million.

In mid-1931, unable to continue subsidizing crop prices in this way, the Federal Farm Board closed. Crop prices plummeted, again. During the winter of 1931/32, many farmers took to burning their crops as coal became more expensive than corn. By the summer of 1932, in Iowa, farmers formed the Farmers' Holiday Association, a militant organization that tried to organize a general farm strike, but was often little more than angry mobs. They occupied courts preventing them from foreclosing on farms and in other cases assaulted judges in attempts to intimidate them from foreclosing.[15] These farmers' riots were occurring at the same time as the Bonus March (see below).

Associationalism (or Volunteerism)

That many Americans were in dire need of basic needs of food, clothing, and shelter, Hoover suggested that Americans rely on self-help and charities. This was part of Hoover's broader philosophy of "associationalism," the idea that Americans would join together in various organizations to help each other and promote their common causes. During the 1920s, Hoover as Secretary of Commerce advocated associationalism as a means for businesses to help each other and this sparked an increase in many industrial "trade associations." As the depression hit, Hoover continued to promote the idea of self-help. Churches, YMCA's, missions, and other community organizations heeded the call by providing the needy in their towns with day-to-day survival. But as the depression went on into its second and then third years, charities found they could not keep up. Donations declined and people had little spare change for a charity and without donations, relief efforts had to be abandoned.

Hawley-Smoot Tariff

As part of his effort to stabilize the farm sector, Hoover advocated higher tariffs. When submitted to Congress in early 1929, the legislature was unmoved. After a fourteen month battle, during which the U.S. entered the recession and the stock market collapsed, Congress finally passed the Hawley-Smoot Tariff. This tariff raised duties on over 70 farm commodities and over 900 manufactures, some to all-time high. Coming as it did about nine months after entering the recession and as unemployment was beginning to mount, Hoover was caught in a bind. His admonitions to business to maintain high wages in order to stimulate consumption meant that he must also offer business protection against cheaper foreign imports. And while over 1000 U.S. economist had petitioned Hoover to veto the bill because it would raise consumer prices, set of a trade war with America's trading partners, and promote economic inefficiency, Hoover felt he had to make good on both his campaign promise and his support of his high-wage policy. Nineteen-thirty was an election year, and Hoover knew he had to back the Republican Party platform then.

Once the tariffs did rise in the U.S., the economists were proved right in at least one area: America's leading trading partners passed similarly harsh tariffs and what was left of U.S. overseas trade dried to a trickle. The tariff did not, however, stimulate price inflation.

1930 election

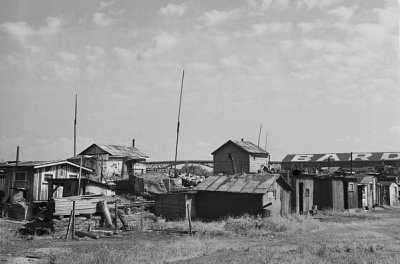

The depression continued to deepen. Millions of Americans were losing their jobs and their homes. Hundreds of thousands were on the road or living in shanty-towns that came to be called "Hoovervilles."

The election of 1930 and the seating of the 72d congress shows the growing concern among Americans about the depression. In the regular election of November 1930, the major issues were prohibition, farm policies, and the Hawley-Smoot Tariff. Economic uncertainty played role, but one that did not severely handicap Republican candidates that fall. In the election, the Republicans retained control of both houses, but just barely. The Democrats made some important gains in this election winning a few dozen seats but the Republicans retained control. But as Congress at this time did not seat its new members until thirteen months after the election, a remarkable shift occurred. During that year, 1931, as the economy worsened, the states held 19 special elections for representatives who had died or had otherwise refused their seats. The Democrats won enough of these special elections that by the time the 72d Congress convened, they had a one-seat majority. In the Senate, the Republicans retained a one-seat majority, but as the depression worsened and as the mood shifted towards legislative action, this one-seat majority was not enough to stall Democratic initiatives. Many Republicans, especially progressives, crossed party lines and voted with the Democrats.

Reconstruction Finance Corporation

With a Congress now intent on passing recovery bills, Hoover also shifted. In 1932, Congress passed the Reconstruction Finance Act which established the Reconstruction Finance Corporation. The RFC was to engage in "pump-priming," which meant that it was to provide hundreds of millions of dollars in loans to banks, building-and-loan offices, home mortgage lenders, life insurance companies, and railroads.[16] With more money available to them, banks would make more loans to business, which in turn would start expansion, putting men back to work, stimulating production, and thus ending the depression.

However, the RFC did not fulfill this role. Chaired by conservative bankers, the money often went to banks able to demonstrate that they did not need emergency funds and could put up the high collateral required by the RFC. The RFC was also criticize for favoritism, a charge that seemed to have some truth when it was revealed that RFC board member Charles G. Dawes's bank received a $90 million RFC loan.

Generally, the lenders that received RFC moneys did not loan it back out but instead used the money to bolster their own reserves. The RFC under Hoover's administration did little to stimulate employment or end the depression, while it did help many banks stave off bankruptcy. But as a semi-autonomous lending institution of the U.S. government, it would play a significant role in the New Deal.

Other Hoover Initiatives

The Glass-Steagall Act of 1932

Continuing the inflationary policy started with the Reconstruction Finance Corporation, the Glass-Steagall Act of 1932 attempted to infuse more money into the economy. This law allowed federal reserve banks to count U.S. securities and commercial paper, in addition to gold, for their reserve deposits. This freed up about $750 millions that banks could infuse into the economy. It staved off further collapse of the economy for the remainder of 1932 but a renewed banking crisis in early 1933 erased any benefit of the law.

Federal Home Loan Bank Act

Passed in 1932 and encouraged by Hoover, the Federal Home Loan Banking Act was to be a lending clearinghouse for savings-and-loans and home mortgage companies. It facilitated the flow of money to mortgage lenders with the intention that easier mortgages would stimulate construction.

The Bonus March

In 1924, Congress voted a pension to every U.S. veteran of World War One of $1,000 payable after twenty years (which would have been 1945). But by 1932, so many veterans were in dire straits that they mobilized a march to pressure Congress to change the law and award the pension immediately. This group of mainly homeless veterans and their families came to Washington, DC. They called themselves the "Bonus Expeditionary Force" in recognition of the name they had in World War One: the "American Expeditionary Force."

By the time the Bonus Marchers reached Washington, they numbered over 20,000. They set up a makeshift "Hooverville" on flats of the Anacostia River south of the Capitol. The House of Representatives introduced a Bonus Bill in June 1932 and approved it. The Senate, however, failed to pass the measure which killed the bill until at least the next year. Many veterans went home.

But thousands of other veterans no longer had any home to which to return. They continued to live in Washington in their Hooverville and began pan-handling workers and tourists at government buildings. Hoover thought the sight of thousands of bums in the nation's capital was a dismal commentary on the nation itself. He pressured Congress to provide funding so that more veterans could buy train or bus tickets home which Congress did just before it adjourned at the end of June.

But still, thousands stayed. Tensions between the veterans and local police escalated. In mid July, while police were clearing a government building, a melee broke out and the police opened fire on the veterans, killing two. After this, Hoover had reached the end of his patience and ordered the commanding general of the military district of Washington, General Douglas MacArthur, to remove the veterans. MacArthur ousted the veterans with a brutality reminiscent of nineteenth-century labor wars. He use cavalry to charge the veterans, burned their shanties, and used gas. One baby died in the gas assault. In his defense of such brutality, MacArthur claimed that this mob of veterans was threatening to overturn the government of the United States. Hoover later charged that "… the march was in considerable part organized and promoted by the Communists and included a large number of hoodlums and ex-convicts determined to raise a public disturbance."[17]

The same month, Franklin D. Roosevelt addressed the Democratic National Convention pledging Americans a "new deal."

The Election of 1932

Prior to the Bonus March fiasco, both the Republican and Democratic Parties held their nominating conventions. The Republicans in a mood despair re-nominated Herbert Hoover. The Democratic Party nominated New York Governor Franklin D. Roosevelt who then did something rather dramatic. He flew to the convention at Chicago and gave an acceptance speech. This is something that presidential candidates routinely avoided because by showing up at the convention they risked tainting themselves with the stigma of the dirty politics that traditionally went on at these conventions. Nonetheless, the move proved dramatic. In his acceptance speech, he said, "I pledge you, I pledge myself, to a new deal for the American people" which became the origin of the phrase.[18]

During the campaign itself, Roosevelt was very guarded about what this new deal would actually entail. It may include something like the Temporary Emergency Relief Administration that he established in New York to put men to work on public works projects. The only other program he talked about was a Civilian Conservation Corps to do land reclamation. But other than these, there were no concrete proposals about what he would do as president. Hoover blasted Roosevelt as a radical who would raise taxes and carelessly spend money.

On election night, Roosevelt won handily over Hoover. He made impressive gains for the Democratic party as well, tallying almost eight million more votes than did the Democratic nominee in 1928 Al Smith. This was an election-to-election increase of 52%. Hoover's popular vote tally, election to election, fell 26% from 1928. Roosevelt's margin of victory, over 17%, was the largest margin of victory over an incumbent president in U.S. history, which is a clear indication of Hoover's unpopularity. Roosevelt also swept into office the first Democratic majority since 1916. It was a Congress in a mood for action.

Franklin D. Roosevelt & the New Deal

Library ID#4796915, Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library and Museum, National Archives.

Upon his inauguration on March 4, 1933, he presented a air of confidence and calm and pledge that he would be a leader of action:

This great Nation will endure as it has endured, will revive and will prosper. So, first of all, let me assert my firm belief that the only thing we have to fear is fear itself — nameless, unreasoning, unjustified terror which paralyzes needed efforts to convert retreat into advance. In every dark hour of our national life a leadership of frankness and vigor has met with that understanding and support of the people themselves which is essential to victory.[19]

The Brains Trust

Roosevelt brought with him to Washington a group of young intellectuals, mainly university types, to begin figuring out solutions to the dire problems facing the nation. As smart as these guys were they offered conflicting opinions about what to do. Some advocated rigorous enforcement of antitrust laws in order to promote business competition. Others said exactly the opposite, that suspension of the antitrust laws would allow business to fix prices, raise profits, and restore prosperity. Others again, thought the focus on business would take too long to bring about immediate relief and they suggest work programs and welfare to relieve the human suffering. With so much diversity of opinion, Roosevelt tried a little of everything.

He could not afford to be dogmatic for a variety of reasons. First, Hoover had been dogmatic in his support of his volunteeristic approach to dealing with the Depression and that proved wildly unpopular. Second, his continued role as leader of the Democratic Party rested on the support of the solid south whose Senators and representatives (because of their lengthy tenure) now controlled the key committees. Dogmatic approaches could easily alienate these powerful legislators. Last, Roosevelt simply was not an idealist. He embraced pragmatism: "It's common sense to take a method and try it. If it fails admit it frankly and try another. But above all try something."

Most importantly coming out of Roosevelt's brain trust was a catchy, but not idealistic, approach to dealing with the depression: relief, recovery, and reform. The programs of the new deal were to provide immediate relief to individuals and families suffering from unemployment and facing difficult financial times. Relief programs would include work programs, like the Works Progress Administration and the Civilian Conservation Corps. Recovery programs were intended to get the economy back on its feet, productive, and profitable. These programs aimed to raise commodity prices and stimulate employment. These programs included the Agricultural Adjustment Act and the National Recovery Administration. Lastly, the advisers developed programs to reform U.S. institutions so that another Great Depression was unlikely to happen. These reforms included changing the banking industry and the stock market.

The Hundred Days

The first session of the 73d lasted ninety-nine days. Few Congresses have so dramatically altered the fabric of the national bureaucracy and economy in such a short time.

Addressing the Financial Sector

The banks of the U.S. faced another round of crisis and closings. On the second day of his administration, Roosevelt declared a bank holiday and closed all the banks in the U.S. Congress passed the Emergency Banking Relief Act in just seven hours after convening on March 9. The EBRA required every U.S. bank to be audited before re-opening. The banks that did re-open on March 13 after the holiday were sound. Roosevelt went before the American people over the new medium of radio to explain his policy through what he called a "fireside chat." While the banking emergency was over, recovery and reform of the financial sector were still needed.

The Glass-Steagall Act and the Banking Act of 1933 of which it was a part, began a wholesale restructuring of the banking industry. Prior to the Glass-Steagall Act, banks loaned to anyone meeting their criteria for loans. This meant that banks were loaning to home-owners as well as to Wall Street stock speculators and to businesses in risky industries. This unregulated loan market meant that individual (known as "commercial") accounts were at great risk as the bank would also be loaning investment money to speculators or industry. If, in an economic downturn for instance, a large business customer could not repay their loan, the default could close the bank and ruin the savings of individual depositors. A main provision of Glass-Steagall required that banks separate their functions. Hereafter, they could be investment banks or be commercial banks but they could not be both. Thus individual, commercial accounts would be protected from risky investment behavior of banks.

Also, in order to protect the individual deposits in commercial banks, the Banking Act created the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation which insured individual deposits for up to $5,000. This meant that even if the bank failed, an individual customer would get back their deposit.

The Banking Act restored public confidence in banks which was something that Roosevelt predicted would happen as he declared in his first fireside chat,

It needs no prophet to tell you that when the people find that they can get their money—that they can get it when they want it for all legitimate purposes—the phantom of fear will soon be laid. People will again be glad to have their money where it will be safely taken care of and where they can use it conveniently at any time. I can assure you that it is safer to keep your money in a reopened bank than under the mattress.[20]

Agricultural Recovery

Roosevelt's advisers, many of them progressives, argued that in modern industrial economies, big business was here to stay. Policies hostile to business (such as trust-busting) were actually damaging to the overall economy. But they also pointed out that the major lesson of the 1920s was that big business was incompetent to operate the overall economy efficiently. They concluded that the best way to maximize production and employment and maintain the economy at peak efficiency was through government guidance and planning. The U.S. experience of World War One when government control, in many industries, led to huge productivity gains reinforced this conclusion. Henry A. Wallace believed that the aim of the New Deal should be "to manage the tariff, and the money system, to control railroad interest rates; and to encourage price and production policies that will maintain a continually balanced relationship between the income of agriculture, labor, and industry." He frankly asserted that laissez faire was a myth: "The hard facts are that for years government has been in business, and business in government, to a point where it is impossible to untangle the mess."[21]

When the policy advisers turned their attention to the problems of agricultural and industrial productivity, they were thinking about the lessons of World War One and the 1920s.

Farmers had been suffering from poor profitability for more than a decade by the time of the New Deal. Hoover's Farm Board had closed up after less than two years of operation having spent hundreds of millions of dollars artificially attempting to buoy agricultural markets. In the four years between 1929 and 1933, agricultural income fell from $6 billion to under $2 billion.

Roosevelt's advisers, just as Hoover's advisers, saw the problem mainly in terms of prices. If prices for agricultural commodities were higher, then farm incomes would rise. Hoover's Farm Board attempted to raise prices by buying crops at artificially high prices but this proved to be a complete failure. Roosevelt's program was the Agricultural Adjustment Administration (created by the Agricultural Adjustment Act). The AAA would pay farmers to keep crops and animals out of production. This would create conditions of scarcity and, if demand remained constant, would raise prices. The funding for the program came from special taxes on agricultural processors (cotton gins, flour mills, grain elevators, and so forth).

This law was passed in May 1933, which led to one of the curious ironies about the New Deal. Administration officials went into the field to enroll farmers in the program right away. This meant that some crops and herds for 1933 had to be destroyed if conditions of scarcity were to be created and if farmers were to accept federal money. For an administration that touted central planning and efficiency, the destruction of food crops during 1933 when hundreds of thousands of Americans were hungry in the cities constitutes one of the unanswerable ironies of the New Deal. Secretary of Agriculture Henry A. Wallace said, "to have to destroy a growing crop is a shocking commentary on our civilization."[22]

By the end of 1934, agricultural commodity prices were up as production was down. Between 1932 and 1935, farm incomes increased by over 58 percent. This increase in income was the result largely in a decline in production, but the AAA was only partially responsible for the decline in production. During the same years, the U.S. suffered a horrible drought called the Dust Bowl. Tens of thousands of farmers, unable to scratch out an existence in the parched earth, up and moved, a tale retold in John Steinbeck's The Grapes of Wrath.

Agricultural Adjustment Administration policies and operations also contributed to this displaced population. The AAA paid agricultural landowners for land taken out of production, but many landowners were not farmers. They leased land (either through a rental or sharecropping agreement) to tenant farmers or sharecroppers. To keep AAA money and the land out of production, these landowners often terminated the rental agreements and kicked the tenants off the property.

There were other problems with the law as well. The AAA was funded through a tax on agricultural processors. This was challenged in United States v. Butler (297 U.S. 1 [1936]). The Supreme Court ruled in 1936 that the AAA encroached upon the powers delegated to the states by the 10th Amendment by using the taxing power to promote an agricultural policy. Because the AAA was accomplishing its desired goal of improving farm incomes, the Roosevelt Administration wanted the AAA re-instated as soon as possible. They re-wrote the law as Soil Conservation and Domestic Allotment Act which based payments to farmers based on soil depletion properties of crops and taxed everyone equally. The law was passed withing six weeks of Butler.

Industrial Recovery

Like the agricultural sector, the industrial sector suffered from low profitability. And like the agricultural sector, the New Dealers believed that their primary goal should be to raise commodity prices. But unlike the agricultural sector, the industrial sector had many millions of unemployed workers. Thus to address the problems of industry, the New Dealers proposed a huge program with two aspects to it.

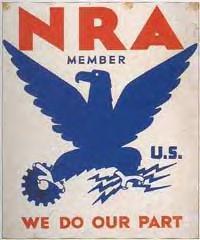

The National Industrial Recovery Act (NIRA) created two programs to address the problems of industry: the National Recovery Administration (NRA) and the Public Works Administration (PWA).

Hugh Johnson directed the National Recovery Administration. The NRA had two main objectives: raise industrial profitability by raising prices and improve consumer purchasing power. To reach both of these goals, the NRA would help businesses establish and follow "codes of fair practice." While the NIRA granted the government coercive power to impose these codes, Johnson was reluctant to use that power lest powerful corporations attempt to block the law through the courts. And given the extremely experimental nature of the program, few within the administration were sure that the NIRA could pass a constitutionality test in the courts. Johnson therefore stressed voluntary participation in the process. Businesses that participated were granted immunity from antitrust prosecution, a powerful incentive to go along. But businesses also had to give up some control over the workplace, allow labor unions to organize, provide higher wages, shorter work weeks, and discontinue child labor. After about six weeks of operation, the NRA had worked out about 200 codes, but given that thousands of codes were expected, higher-ups in the Roosevelt Administration began chafing at the slow rate.[23]

Labor practices were seen as an integral part of the deflationary problem. In a world where businesses were forced to compete, their rivalries put downward pressure on wages. Depressed wages, lowered consumption, which again put greater pressure on businesses to compete. It was a viscious downward cycle. By guaranteeing wage stability through collective bargaining, this downward pressure on profitability would be avoided.

By the end of July, the Administration tried to jump-start the code writing process through public pressure. Keeping with the administration's desire to promote voluntary participation as much as possible, the public relations campaign pressured businessmen to agree to a "blanket code" called the "President's Re-employment Agreement." Over two million employers signed up. The President's blanket code required that employers pay minimum wages (between $12 and $15 a week depending on local costs of living), limit the number of hours to 40 hours per week for full-time employment, ban child labor, freeze current wages, limit price increases, and support the NRA by buying only from other NRA participating firms. For decades, Progressives were seeking minimum wages, shorter hours, and an end to child labor and had succeeded here.[24]

Following implementation of the blanket code, Johnson encouraged the crafting of individual "codes of fair practice" for each industry. Most of the codes were written by the industry trade associations in consultation with government and labor bodies. By the time the NIRA was declared unconstitutional, over 500 codes had been written and approved by the NRA. Johnson wished to show businessmen that they had nothing to fear from the NRA and so granted business nearly everything that they wanted in these first codes. The government essentially offered business a sanctioned cartel in exchange for improvements in workers' standards of living.[25]

Public relations continued to be a significant part of the NRA as businesses that participated in the program and followed their industry code were allowed to display a blue eagle on their product or place of business. The Blue Eagle proudly proclaimed that "We do our part" in fighting the economic emergency. The implication was that patriotic Americans would buy products from manufacturers "doing their part" for the nation's economy.

The law was fraught with divided purposes and confusion. For instance, while the NIRA granted immunity from antitrust prosecution to those firms that participated in the program, the law did not fully exempt firms from monopolistic behaviors. Very quickly, the trade associations writing the codes understood that they could impose price floors (that is, engage in price fixing) for products and nearly every code did. Administration officials expected firms to continue to compete, even though their NRA codes eliminated much price competition.

Firms also soon discovered the difficulty in enforcing the codes. Firms seeking to turn a quick profit could undercut their competitors in the market by offering products at below-code prices. This sort of cheating was often reported to the NRA for enforcement, but with over 30,000 violations before it for investigation by 1935, the NRA was quickly overwhelmed. As it became clearer that the NRA was a weak policeman of the system, non-compliance increased. The NRA, for its part, was in a difficult political position. If it wished to enforce the codes, it would have to argue for enforcement of policies that harmed consumers which would have been upopular with both courts and voters. And many NRA administrators still had doubts about the constitutionality of the law and wished to avoid any showdown in a court.

Trade associations tended to be dominated by the largest firms in their industries. General Motors tended to dominate the automobile sector just as United States Steel tended to dominate the steel industry. The NIRA, following the views of its Progressive authors, attempted to protect smaller businesses from the overwhelming economic might of big business. The law and NRA codes could not "eliminate or oppress small enterprises," and large firms attempting to drive out the smaller would find themselves outside the law.[26] Nonetheless, trade associations wrote codes that were more beneficial to their dominant members than to their smaller members.

While labor did gain the right to bargain colletively for wages and while maximum hours and minimum pay were guaranteed by NIRA, it is not clear that labor gained much more than that. Because businesses could and did, operate more cooperatively as a cartel, they were also better able to resist union demands. But what the labor recognition clauses did accomplish was the establishment of basic employment norms such as the minimum wage, the forty-hour workweek, and the ban on child labor.

Economists, however, seem to believe that the NRA by attempting to keep both prices and wages high, that is, by being an inflationary program, kept the deflationary pressures of the economy from running their course and prolonged the depression.[27]

On May 27, 1935, the Supreme Court ruled in Schecter Poultry v. U.S. that the power that NIRA gave to the NRA to write economy codes was an unconstitutional delegation of Congress's legislative power to the executive branch. As there was by this time widespread non-compliance and cheating among business, and that the NRA had lost a lot of the respect that it had started with, and as it had failed to dent the high unemployment, the Roosevelt Administration made little effort to revive the program in any wholesale way as it had for agriculture. Nonetheless, some sectors did benefit from the sanction cartelization that occurred under the NRA and sought to continue it. Congress during the remainder of the 1930s passed what became known as the "Little NRAs" these included the Robinson-Patman Act for small retailers, the Guffey Acts for bituminous coal operators, and the Motor Carrier Act for truckers.[28]

Public Works Administration

The law granted the PWA $3.3 millions for the construction of buildings, highways, flood control projects, and other capital improvements. The aim was that these construction projects would employ millions of the unemployed. The PWA was under the supervision of Secretary of the Interior Harold L. Ickes. Given the nature of these projects, Ickes wanted well-built and lasting construction, not slap-dash make-work. He used private contractors who were experts in their fields, and they did the hiring. Some major accomplishments of PWA projects were New York City's Triborough Bridge, Florida's Overseas Highway, Chicago's subway system, and Virginia's Skyline Drive.

Employment Relief

Hoover believed that any hand out from the government (the "dole") would instantly lead Americans into idleness and sloth. He refused to endorse any program of direct government assistance (thus his support of the Reconstruction Finance Corporation which was indirect). Roosevelt and his New Dealers wanted to have programs of direct assistance, but they, too, avoided simple hand outs. Federal Emergency Relief Administrator Harry Hopkins advised state agencies to follow an "immediate work instead of dole" approach to using federal money. Furthermore, there was a constitutional test in that direct aid was a responsibility (if given out) of the states and not the national government. Many states by this time had created direct aid agencies. New Deal programs that sought to provide aid (such as FERA) worked with these state agencies through federal grants.[29]

Within a month of taking office, Congress passed both the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) and the Federal Emergency Relief Act. The CCC was for young men between the ages of 18 and 25 who could have their parents vouch for them. They were organized in camps in areas in need of land reclamation. They worked on soil conservation and reforestation projects, but also built public parks, campgrounds, bridges, fish hatcheries, work with farmers to fight soil erosion, and fought forest fires. They were paid $30 a month, but $25 of that was sent to their parents. Nearly 3 million men were enrolled in the CCC, but because of the need to placate southern congressmen, the CCC was open to white men only.

The Federal Emergency Relief Administration (FERA) was much like the CCC, except open to all men, and for which they got paid directly. The FERA did much of the same work building bridges, roads and parks, but also constructed and repairing highways, public buildings (including schools and post offices), constructing sewer systems, and airports. The FERA was a mixed federal-state program: it gave money to states to fund these sorts of works projects for unemployed men. Thus Harry Hopkins, the administration's director, kept pushing the states to use the money to put men to work instead of just doling it out to the unemployed. Also because FERA relied on state action to put men to work it worked as quickly—or as slowly—as the states wanted.

By November it was clear that FERA was not employing men at a high enough rate to forestall a crisis during the winter of 1933/34. Roosevelt therefore created by executive action the Civilian Works Administration, which was the first federal work relief program. It funded the sames sorts of building projects as FERA did, but employed men directly. During that winter over 4 million men worked for the CWA but at a staggering cost. By March 1934, the program had spent over $1 billion, a figure which startled the president. With the winter emergency passed, and the program clearly being an expensive drain on the federal budget, the program was canceled in April 1934.

Did the First New Deal Promote Recovery?

Economists and historians are rather mixed on the degree to which the First New Deal promoted recovery. By 1933, the economy after three years of solid decline had few directions left to go but up. Recent work by economists suggests that monetary policies had more impact on the economy than any other. Ben Bernanke, for instance, argues that recovery began for economies once they abandoned the gold standard, which the U.S. did in mid-1933.[30] Christine D. Romer notes that most industrialized nations hit by the depression seemed to hit bottom and turn at about the same time, between 1932 and 1933.[31] In the areas of agricultural and industrial recovery, current interpretations suggest that the inflationary aims of the AAA and NIRA inhibited the economy from self-adjusting. In the areas of banking and finance, the changes did stabilize the sector and promote recovery.[32]

By mid-1935, the two cornerstone programs of the New Deal, the AAA and the NIRA, had been declared unconstitutional by the Supreme Court. While the AAA seemed to have raised farms incomes and was restarted under different legislation, widespread cheating and dissatisfaction with the industrial recovery program led the Roosevelt Administration to let that program die. Prices and production were rising which indicated a recovery, but incomes were stagnant and unemployment was still high. After two years, with modest results and still massive unemployment, it was clear that the New Deal was beginning to eat into Roosevelt's chances for re-election.

And then complaints began to get shrill.

Voices of Protest

If Roosevelt's economic policies did little to alter the course of the depression, his personality, charm, and openness to the American people earned him a lot of support. Roosevelt gave press conferences twice a week, periodically addressed the nation through his "fireside chats" and traveled and spoke throughout the country. His availability to the American public was a significant shift from the stilted and aloof character. This charm translated into political power during the 1934 election when the Democrats won over 90 more seats in the House and 11 seats in the Senate.

As the economy limped along, many were becoming more outspoken in their criticism of the President. Milo Reno, the North Dakota leader of the 1932 farm revolt complained, "We were promised a New Deal. We have the same old stacked deck."[33]

Liberty League

In May 1935, the same month that the Supreme Court's Schecter decision, the U.S. Chamber of Commerce began vocal criticism of the New Deal. With this shift, the president had lost the support of business.[34]

Former presidential candidates John W. Davis and Alfred E. Smith along with conservative industrialists such as John Jacob Raskob organized the Liberty League. With funding from America's largest corporations, the League organized a propaganda campaign against the New Deal. Spending twice as much money as the Republican Party did in 1935 on press, the Liberty League denounced every New Deal program as a march towards tyranny and socialism. It labeled the AAA as a "trend toward Fascist control of agriculture" and social welfare programs "the end of democracy." Congress was becoming "little more than that of the present Congress of the Soviets, the Reichstag of Germany, or the Italian Parliament."

In January 1936, Al Smith gave a radio speech at a banquet of the Liberty League in which he denounced Roosevelt, the New Deal, and liberal Democrats as communists. "There can be only one capital, Washington or Moscow. There can be only one atmosphere of government: the clean, pure, fresh air of free America, or the foul breath of communistic Russia." The Roosevelt Administration countered afterwards that "it was the swellest party ever given by the du Ponts" pointing out that this was the message of the wealthy in America, a class of people that millions still blamed for the depression in the first place. The administration was easily able to discount the Liberty League as well-to-do malcontents while the administration was doing something for the common man. As such, Roosevelt's popularity began to rise dramatically after Smith's speech.[35]

Father Coughlin

Charles Coughlin was a Catholic priest of a parish in Royal Oak, Michigan. Because of anti-catholic hostility in Royal Oak during the 1920s, Coughlin arranged with a local radio station to broadcast his sermons weekly. As the depression hit, Coughlin's sermons took on a decided political and economic angle. He told people that the depression was more than an economic downturn; it was a contagion of human suffering and in invitation to redefine and restructure the American society. At first he denounced few by name, identifying the problems as "greed" or "bankers." But by 1931, Couglin was placing blame for the human suffering on Hoover. During the 1932 election, Coughlin was a supporter of Roosevelt and carried his enthusiasm into the summer of 1933 with such slogans as "Roosevelt or Ruin" and "The New Deal is Christ's Deal."[36]

But by the end of 1933 and certainly throughout 1934, Coughlin's enthusiasm waned as it was clear that the New Deal wasn't ending the human suffering fast enough. Coughlin moved to more radical policies than Roosevelt was willing to countenance, such as the remonetization of silver and government take-over of the Federal Reserve. His views continued to drift further from the President. In November of 1934, he started forming National Union for Social Justice societies. While it wasn't a very structured organization, they sprang up everywhere and historian Alan Brinkley call it "something very close to a third party, supporting candidates and attempting to influence elections."[37]

Huey Long

The liberty league, as the first widespread outspoken critics of the president, tended to inspire other critics. But these later critics tended to come from the left, have much greater grass-roots and popular backing, and posed a serious political challenge to the President.

Elected to the governorship of Louisiana in 1928, the same year that Roosevelt was elected governor of New York, Huey Long used the power of state to expand services to people, such as a free textbook program for the schools and scholarships for higher education. During the depression, he instituted public works projects building roads, bridges, and schools. Long was a pugnacious politician, feuding often with the legislature and various other political opponents. He ran the state as his own political party, often taking bribes and kickbacks for contracts and political appointments. While his administration was corrupt, he often played to the hearts of the people, noting how he took on the big oil interests in the state to fund his public works projects. In 1930 he ran for and was elected on the strength of his popularity to the U.S. Senate.

In the Senate, he was a constant critic of Herbert Hoover as a president who did little for people in distress. During the 1932 election he backed Roosevelt and was expected to be an important supporter for the New Deal in the Senate. Long, however, was soon disappointed. New Deal measures to support the banks (such as the Banking Act) and big business drew his ire, although he supported New Deal work legislation such as the CCC. By January 1934, Long inaugurated his "Share our Wealth" campaign. It was a program of regressive taxation on the wealthy coupled with liberal household and pension guarantees (every household in the U.S. would be guaranteed a $2,000 annual income from the tax). He encouraged Americans everywhere to organize "Share Our Wealth" clubs and this became then the basis for his nationwide movement. On the speaking circuity few orators ever compared with Long. H. L. Mencken even ranked William Jennings Bryan behind Long in terms of persuasive oratory.[38]

By the summer of 1935, the Long organization was claiming over 7 million followers to the Share-Our-Wealth clubs.[39] Many followers were talking about a third party challenge to the Democrats and Republicans and many in the administration were taking this threat seriously. Roosevelt's chances of re-election were not all that certain.[40]

Francis Townsend

The last of the major grass roots movements to dogged the president was the Townsend Plan. This was a proposal for an old-age pension that would also serve as an economic stimulus. Francis Townsend, the elderly doctor who came up with the plan, believed that if the government paid every American over the age of 60 a $200 pension and if they were required to spend the money within one month of receiving it, it would reduce unemployment, stimulate consumption, and revive the economy. The pension would be funded by a national sales tax. Townsend organized "Townsend Clubs" to popularize the plan and lobby Congress. The clubs were so powerful during the 1934 election that many Congressmen owed their election to these clubs. At least one bill was introduced, along with the Social Security Bill, to create a Townsend-style pension plan.

The Roosevelt Administration did not like the Townsend plan. The Committee for Economic Security and others in the Administration thought that the national sales tax would be a drag on the economy. The pension rate ($200 per month) was also seen as too high.[41] Yet they did not want to dampen the enthusiasm for a national pension plan, either. The Townsend clubs created a political environment where passage of a national pension became a priority. Many Townsendites however felt that the president's plan did not go far enough to address the needs of the elderly or to promote general economy recovery and began organizing with the Long and Coughlin forces during 1935.[42]

The Second New Deal

The popular support behind these men and their proposals worried Roosevelt. The Coughlin and Long organizations were even making plans to become a third political party. That so many Americans were behind the ideas of Social Justice, Share Our Wealth, and Old Age Retirement showed that there was a lot of grass roots support for this leftward social welfare programs. And since this seemed to be where the votes were, Roosevelt decided to follow. Besides, the programs of the New Deal, the AAA, the NIRA, and others, were slow in bringing about recovery. Some, like the NRA, were a dead letter. The political imperative, if nothing else, impelled Roosevelt to offer a new set of programs and proposals.

This second set of programs differs enough from the legislation of the Hundred Days that historians have called this the "Second New Deal" although neither Roosevelt nor other politicians at the time called it that.

The programs of the second new deal were intended to play to the vast population of the United States that had marked their dissatisfaction with affiliation with Coughlin's, or Long's, or Townsend's groups. The programs of the second new deal were more blatantly class oriented, aiding the middle and working class at the expense of the upper class. This legislation included a Holding Companies Act to more strictly regulate big business, a regressive income tax on the highest tax brackets, a National Labor Relations Act (sponsored by Senator Robert Wagner and called the Wagner Act) that protected workers rights to organize labor unions. He re-initiated a Project Works Administration to continue the work of the PWA that had been declared unconstitutional with the NIRA. The last important measure of the second new deal was an old age pension plan called Social Security.

To a Hearst organization reporter (Hearst hated Roosevelt), Roosevelt explained, "I am fighting Communism, Huey Longism, Coughlinism, Townsendism. I want to save our system. To combat this [he was referring to Long's Share Our Wealth program] and similar crackpot ideas it may be necessary to throw to the wolves the forty-six men who are reported to have incomes in excess of one million dollars a year."[43]

The President's Committee on Economic Security

This committee was chaired by Frances Perkins.

The Social Security Act

"In 1935, some 20 nations around the world already had such a program in place, and another 30 or more had introduced at least one other social insurance program (for example, workers' compensation)"[44], out of roughly 100 countries.

The New Deal and Changing Expectations

By the time of the Second New Deal, Roosevelt had begun changing American expectations of their government. Some programs, such as the Agricultural Adjustment Act were expected to become perpetual, a new function of the national government. And if the national government was expected to efficiently manage crop production, should it not also help Americans with their savings? Social Security too was envisioned to be a permanent new function of the national government.

Notes

- ↑ The editors of the British journal The Economist have suggested that the term "depression" is conventionally applied to a decline in real GDP that exceeds 10%, or one that lasts more than three years (See "Recession, Depression—What's in a word?" The Economist [UK], January 5, 2009). But despite this definition, The Economist also noted that prior to the Great Depression any economic recession of any severity or length was called a "depression." Economists since 1929 have used the term "recession" in preference to "depression" "to avoid stirring up nasty memories." reference note from the Citizendium, original author Russell D. Jones.

- ↑ For a full-length investigation of the influence of Progressive Era reformers on the New Deal, see Otis L. Graham Jr., An Encore for Reform: The Old Progressives and the New Deal (New York, Oxford University Press, 1967).

- ↑ Paul A. Samuelson and Everett E. Hagen, After the War, 1918-1920: Military and Economic Demobilization of the United States (Washington, D.C.: U.S. National Resources Planning Board, 1943), 13; Atack and Passell, 2d ed., 555.

- ↑ Atack and Passell, 2d ed., 557

- ↑ U.S. Census Bureau, Historical Statistics

- ↑ Atack and Passell, 2d ed., 562.

- ↑ John A. James and Richard Sylla, "Table Ce13-41 - Personal saving, by major components of assets and liabilities: 1897–1949 [Goldsmith]," Historical Statistics of the United States, Millennial Edition, ed. Richard Sutch, and Susan B. Carter (Cambridge University Press, 2010).

- ↑ John A. James and Richard Sylla, "Table Ce13-41 - Personal saving, by major components of assets and liabilities: 1897–1949 [Goldsmith]," Historical Statistics of the United States, Millennial Edition, ed. Richard Sutch, and Susan B. Carter (Cambridge University Press, 2010).

- ↑ Bruce L. Gardner, "Table Da1288-1295. Farm income and expenses: 1910-1999," Historical Statistics of the United States, Millennial Edition, ed. Richard Sutch, and Susan B. Carter (Cambridge University Press, 2010).

- ↑ Roger A. Pielke Jr., et al., "Normalized Hurricane Damage in the United States: 1900–2005," Natural Hazards Review 9, no. 1 (February 2008), 29-42, DOI:10.1061/(ASCE)1527-6988(2008)9:1(29), Natural Hazards Review is a publication of the American Society of Civil Engineers.

- ↑ This account of the 1920s real estate boom is mostly from Frederick Lewis Allen, Only Yesterday: An Informal History of the 1920s (New York: Harper & Row, 1931; repr. John Wiley & Sons, 1997), chapter 11 "Home Sweet Florida," but see in particular, pp. 206, 210, and 213.

- ↑ Frederick Lewis Allen, Only Yesterday: An Informal History of the 1920s (New York: Harper & Row, 1931; repr. John Wiley & Sons, 1997), 219.

- ↑ Couch and Shughart, 8; Hall & Ferguson, 7.

- ↑ Herbert Hoover, The Memoirs of Herbert Hoover, vol. 3, p. 30.

- ↑ There is little work done on the Farmers' Holiday Association. The records of the organization are held by Iowa State University.

- ↑ While railroads were not lenders, and thus not expected to loan out the money they received from the RFC. Railroads were expected, however, to be one of sectors leading the recovery

- ↑ Herbert Hoover, The Memoirs of Herbert Hoover: 1929-1941, vol. 3: The Great Depression (New York: The Macmillan Company, 1952).

- ↑ Franklin D. Roosevelt, "Address of Governor Franklin D. Roosevelt Accepting the Presidential Nomination," delivered before the Democratic National Convention, Chicago, Illinois, July 2, 1932.

- ↑ Franklin D. Roosevelt, First Inaugural Address, March 4, 1933.